There are several aspects of the situation of the Night’s Watch that we are introduced to pretty early in the story. In the beginning of “A Game of Thrones”, Benjen Stark mentions that there are many deserters. We soon learn that the Gift is scarcely populated, that the Raiders are growing bolder and getting over the Wall all over the place, that most castles are empty (16 of 19, to be exact) and that the Night’s Watch barely possesses enough men to garrison their remaining three castles. In fact, their main seat, Castle Black, is in a state of frenzied decay, with several buildings uninhabited for decades and nearing collapse. Even more often, we are told about the glorious past days of the Watch, when eighteen castles were manned (they never manned all 19 since Queensgate was built to replace the Nightfort) and one man in every ten was a knight, instead of one in every hundred. Man, that had been times! Thousands of black brothers, armed to the teeth, highly trained and motivated to fight off rag-tag bands of raiders, because the last King beyond the Wall dates back before the Targaryen conquest. And then, in the course of 250 years, the Watch declined to its present sorry state. From eighteen castles to three, from thousands of well supported men to a rabble of perhaps a thousand, if you count the stable boys.

|

| It stood for thousands of years! |

|

| That one. |

So, after this caveat, back to topic. Why is the realm guilty of ruining the Night’s Watch? To explain this, we have to look at its ancient roots. In the beginning, the main purpose of the Night’s Watch was to fend off the Others, as evidenced by the Wall itself. As Mormont rightly states, no one builds a Wall that high just to fight some raiders. But the Others have slept since the Long Night, so this purpose was more and more forgotten, and as the lands beyond the Wall ceded to be No-Man’s-Land, people started living there – the wildlings. Some of them might actually have always lived there and somehow endured the Long Night, some others might have migrated, but it doesn’t really matter. The Night’s Watch started to defend the northern lands against the wildlings, because what else would they do? Fight Grumpkins and Snarks? But that presents us to our first mystery. The danger posed by the wildlings affects the lands of the Umbers and the Karstarks most of all, perhaps extending as far as the Bolton, Mormon and Glover lands, but the great kings beyond the Wall aside, I highly doubt that Winterfell or White Harbor were ever threatened by wildling raiders, much less any lands south of the Neck. So, why did any king or lord or knight from south there ever join the Night’s Watch or support it?

|

| Other than getting rid of a "beloved" son, of course. |

And this support is not to be taken lightly. Yoren mutters in “A Clash of Kings” that in earlier times, a black brother was welcomed at all tables in Westeros, an honored guest, and helped along his way. But why? What did anyone gain by supporting an order that simply protected the lands of some lords and kings far, far away? And, even more to the point, why did the Andals continue to do so after they conquered most of Westeros? This last point is, again, crucial. One could argue that the Night’s Watch was a common institution of the First Men, that they did somehow transport the knowledge and legacy of the Long Night for two thousand years and that this was enough to keep it, although that is highly unlikely. But the Andal invasion conquered the whole of Westeros except for the North, the very location where Wall and Night’s Watch were situated. The only lands the Night’s Watch could realistically protect belonged to the common enemy of all Andals!

|

| Under their damn seven-sided-stars. |

Here we come to the crucial point. The Night’s Watch serves a critical function in Westeros, or rather served. We know from numerous accounts that the kingdoms of old were warring amongst each other all the time. This didn’t exactly cease with the Andal invasion. The Andals carved out their own kingdoms, and soon enough, after defeating First Men and Children of the Forest alike, they began squabbling among themselves about the spoils of victory, created their own houses and kingdoms, married into surviving First Men nobility and certainly inherited some of their strives as well. Did they come to accept the Night’s Watch as a “Westerosi” institution? Like the laws of hospitality, that they also accepted from the First Men?

|

| Which of course are not what they were. |

They did, but this decision was helped along by an important service the Night’s Watch had offered to the warring nobility for millennia (if the accounts can be believed). Imagine a petty lord or king, fighting his neighboring petty lord or king. What we know (and can believe) of family histories is that most families’ primary goal was to survive, to keep the family name, as Tywin Lannister put it in HBO’s series. That means that all these wars they fought cannot have been fought with the goal of extermination in mind. Take the Blackwoods and Brackens as a case in point. Both of them fought at least for centuries against each other, but never once came they close to exterminate each other. Many other such conflicts likewise didn’t end with decisive results. Instead, most of the time stretches of land were swapped, hostages exchanged, humiliations delivered and raids conducted. These times must have been even more gruesome for the smallfolk then what we witness in the Song of Ice and Fire proper.

|

| The Bracken sigil, for lack of a better image. |

But for the nobility, self-preservation rules that when you fight so many wars and skirmishes over so little achievements, you don’t want to be those battles fights for life and death. So, let’s assume the Brackens want to fight the Blackwoods over control over a certain mill and send their third son as commander of a small unit of soldiers, perhaps 20 to 30 men. Our Ser Whatsit of Bracken rides forth and meets Ser Whocares of Blackwood, the fourth son of King Blackwood, in battle. Both of them fight along, merrily splitting the heads of their lowborn soldiers who die screaming in the Riverlands mud, and finally meet for duel. Both of them are armored heavily, as befits knights, so like as not the fight ends with one yielding instead of taking the smallfolk’s route of dying with a smashed collarbone. Perhaps a knight even yielded to some clever tactic, like an ambush or something. The battle has been decided in all its glory, so what to do now with Ser Whatsit? Why, he takes the black, of course. Like as not, he has kin on the Wall from previous such adventures he itches to see again anyway. For Blackwood and Bracken, that serves the purpose. They didn’t lose overly much in the conflict – the smallfolk doesn’t count at all, and Ser Whatsit is the third son who pisses off the heir all the time anyway -, but since you want someone who actually takes these petty fights, the risk of dying should be as minimal as possible, with some attractive prospect for the loser.

|

| Usually not allowed to take the black but murdered. |

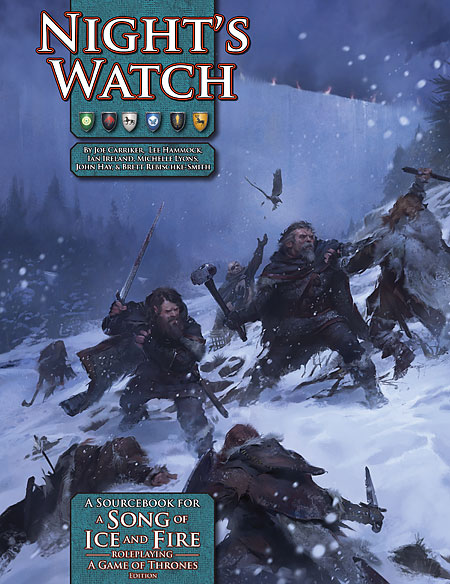

Now take what we know of the Night’s Watch of old. One in ten of the black brothers was a knight, which makes for a larger number of knights at the Wall than in any army that is brought on the field in the rest of Westeros! The Wall is practically a knight order. Some giant club of knights, hanging out in a rather inhospitable but cheap place. Remember that scene in “A Dance with Dragons” where the shield hall in Castle Black is described? It has stood empty for ages, but once only the knights (!) sat in there, hanging their shields proudly on the wall. And that hall was huge, providing space for black brothers, queen’s men and wildlings! And Castle Black isn’t even the biggest castle at the Wall. That means that if the black brothers of old weren’t all distant relatives of Harren and built too big, they really had that many people there. Now, Lord Commander Mormont mentions that in days past, the Haunted Forest was cut back all along the Wall by the black brothers and that sometimes castles went to war with each other. That strongly indicates some kind of rivalry between the different castles, which also explains the inflated number of eighteen along the Wall and why it was so important they had no defenses pointing south: the Night’s Watch’s first and foremost purpose in those millennia was to keep all those highborn losers occupied, and a clever Lord Commander used that to his advantage.

|

| Accurate reconstruction of what happened in the Watch of old. |

I put my money on the fact that the castles were inhabited by origin. For example, one castle was made up of all those nobles who disliked the nobles of another castle. Let’s assume (as a thought experiment) that Blackwoods always served at Woodswatch-by-the-Pool, while Brackens served at Sable Hall. Boltons also went to Woodswatch-by-the-Pool, which in turn meant that no sane Lord Commander would ever send a Stark there, and so on. That way you guarantee that all castles consider the others as rivals, but – and that’s important – not as enemies. The oath of the Night’s Watch binds them all together, and the punishment for attacking or even actively damaging another brother is the same as desertion – death, carried out swiftly, and, even more importantly, disgrace. Since fighting wildlings is a bit of a lame exercise if you have over a thousand knights at your command, such rivalries and the inevitable contests that followed created a win-win-situation: the Watch was all the richer for it, and the nobles could gain honor and prestige. Whose castle best trims back the Haunted Forest? Whose section of the Wall shows the least cracks? Who comes up with the best trained garrison? The list is endless.

|

| Who has the biggest direwolf pet? This round goes to...Gilly! |

That way, losing a battle and taking the black isn’t a hard fate for anyone who isn’t the heir of his house. Heck, in many cases, they will have looked forward to it. And since every house had members on the Wall that tried to outdo other house members in honor and, one can assume, reported back with some regularity, not supporting the Watch would have been a really bad move for any house, be it of Andal or First Men descent. If you deny the Watch a request for supplies and such, or men, or safe passage, you dishonor yourself, because it’s more or less like not honoring guest right. The high percentage of nobles also means that the black brothers travelling the realm wouldn’t have been Yorens, but rather Benjen Starks, recruiting highborn to their cause. It is not entirely impossible to imagine that many of the lowborn members of the Watch were brought with the highborn members.

|

| Immediately before taking the oath. |

This leads us to the Gift. Brandon’s Gift, the only Gift in those days, has virtually no inhabitants. But it was richly cultivated land. Most brothers of lowborn descent will have worked either as builders or stewards, leaving the fighting to the highborn lords and knights and only supplementing them like men-at-arms supplement a knight. The Watch is therefore less dependent on taxes in kind, because they have enough stewards who work the Gift. The whole Watch has therefore a surprisingly high amount of members that basically are peasants, working the whole day on the field. The Watch of old was much more self-sufficient than the new Watch is.

|

| They had all kinds of shitty jobs for the smallfolk back then. |

I have now painted a vivid image of just how the glory of the old Night’s Watch must have looked like, with many nobles engaged in an order-like institution, vying for honor and glory in endless rivalries and contests. This explains the high number of castles, the high number of brothers, the high regard the Watch had in Westeros. It also explains their rapid decline after Aegon’s Conquest. What killed the Night’s Watch is the King’s Peace.

Before Aegon conquered Westeros, there were (at least) seven kingdoms, with vassals enjoying a greater autonomy than today. After he finishes his conquest, there were two kingdoms (Dorne and the rest) and the Warrior’s Sons and the Poor Fellows were soon to be disbanded. Aegon’s power (and the power of every other king on the Iron Throne) derives of the usual compact between vassal and overlord: service against security. The vassals swear their swords and obedience to the king, who in turn promises to keep them safe and be fair. A king who cannot protect his subjects is no king at all, as is emphasized time and time again in the books. The King’s Peace, therefore, forbids any war between the lords. All strives have now to be brought before the overlord, and in many cases, that means the king. He then decides, and his verdict is final. There is not only no need any more to fight over every mill you want to claim, it is also expressly forbidden. People who still fight are sent to the Wall, too, but as rebels. There’s no honor in that. Accordingly, the number of nobles joining the Watch drops dramatically by factor 10, from 10% to 1%, and those 1% are rebels and other perpetrators in most cases and not interested in honor anymore. Since we have previously established that many nobles most likely brought some of their own people with them to take the black together with them, that means a sharp decline in lowborn brothers as well (although not as sharp as with nobles, since the Watch quickly adapts and starts to take in everything it can get, especially convicts).

|

| Like him. |

Only some 50 years into Aegon’s conquest, this decline makes the Nightfort unsustainable, which has been the pride of the Watch for millennia. Only Good Queen Alysanne’s jewels allow them to build a replacement castle, Queensgate, although there really is no reason for it. Consequently, Queensgate is abandoned within a decade of its completion, a monument to the old way of thinking that no longer is appropriate to the Watch’s ressources. In quick succession, other castles that have only thrived on contest and rivalry are given up. The Watch starts to rationalize. No one needs Westwach-by-the-Bridge, because on the other side of that bridge, the Shadow Tower looms and is much easier to defend. No one needs Woodswatch-by-the-Pool and Sable Hall within half a days ride of each other, so the wooden castle Woodswatch goes. And so on, until three castles remain: the logistical hub of Castle Black, strategically placed on the end of the Kingsroad (other than the purely representative Nightfort, that was once built at the place of the Black Gate that no one remembers anymore) and the eastern and western endpoints of the Wall, respectively.

|

| Westwatch-by-the-bridge and the Bridge of Skulls. |

Accordingly, the Watch had too few men to sustain Brandon’s Gift anymore. All hands were needed to defend the Wall, administer the supplies and fend off wildlings. Good Queen Alysanne had a solution for that as well and doubled the Gift, including areas formerly held by Umbers and Karstarks that sported some smallfolk living there that now paid its taxes in kind to the Watch for their support, as Bran recites so adoringly to Benjen. But the decline of the Watch and the reduction on three castles meant that the protection against wildlings, which hadn’t been an issue in the old days (except when some strong leaders actually devised cunning plans), wavered. The people left the Gift, leaving the Watch with long leagues of unpopulated and useless land since they didn’t have the people anymore to work it.

|

| Need them all to tend ravens. |

And that’s the situation that we find in the novels, a dismal state, brought on the Watch by the King’s Peace. The rabble of the kingdoms mans the Wall, except for some few houses that still consider the Watch as an honor (Royce, Mormont, Stark, among some others) because they generally follow the old ways a little bit more than the others, who have quite accommodated themselves with the rule of the Iron Throne. Said rule also puts the responsibility for protecting the North against the wildlings in the hands of the lord of Winterfell, further distancing the Watch from the hearts and minds of the people in the other kingdoms. There is nothing that can improve this situation for the Watch other than what Jon is doing: making common cause with the wildlings, instead of fighting them. Since this has so long been the duty (and before that, sport and pastime) of the Watch, this is of course a little bit difficult to pull off, but such uncomfortable decisions must be made by those who live in the past too long, don’t read the writing on the wall and deny reform. And that’s exactly what the Watch did since Aegon’s Conquest, and accordingly, they suffer for it.

Very good analysis, sounds fully convincing to me and gives some much-needed background - if only we could read book 6 now!

ReplyDeleteI was wondering about this the other day when I was re-reading Jon's AGoT chapters. Maester Aemon was talking about Harren's brother having 10,000 swords at his command when Aegon I immolated Harrenhal and it just seemed amazingly high compared to the less than a thousand figure we've been given for recent times, 300 years later.

ReplyDeleteRaymun Redbeard was the most recent King Beyond the Wall and his march south was around the ~first Blackfyre Rebellion, I think. Although, the Watch missed the main battle and were ordered to clear up by Artos the Implacable but I'm sure they had to face some retreating raiders as they made their way back toward the Wall. So I'm not sure they suffered many losses at all.

Love the blog, dude. Keep up the good work.

KC

This is great! Goes right in line with my re-read - bran and the gang are at the Nightfort currently.

ReplyDeleteOne squabble over a nerdy detail - and I could be wrong - but in my current re-read, Im fairly certain Deep Lake was built as a smaller, cheaper replacement for the Nightfort and was paid for by the Queen. That same Queen is who the Watch renamed Snowgate to Queensgate for - it was an already existing castle, just renamed in her honor

Very well possible, I did the article out of my head.

Delete