There was fantasy before „A Song of Ice and Fire“, and there is fantasy after it. Martin’s yet unfinished epic marks a turning point in a genre that seemed to be stuck in the corner for children and nerds forever. Dragons, mages and heroes were abundant. While some authors experimented with other scenarios, the majority still saw „good vs. evil“ as a driving force behind fantasy. It was Martin who changed that forever and inspired a flood of „dark“ fantasy that has grown so dominant that many people start to ask if there could be a fantasy world without obscenities and racism. However, few reached what Martin achieved. The new cliché is not the radiating hero, but the anti-hero cursing and fucking his way through hordes of enemies instead. That’s of course not what makes Westeros such a grim place. While it has its fair share of curses, sex and violence, it’s the often quoted „gritty realism“ that makes it such a great literary place – and the implications for our own minds that make it such a rich story to explore. The most striking example for this is the pervasiveness of the feudalist system.

|

| Not exactly a socialist revolution. |

This may come as a surprise at first. Isn’t feudalism the standard political system in fantasy? I mean, the Lord of the Rings has kings and nobles, too, right? Peasants labor in almost every fantasy world. This is true, and at the same time it is false. While most fantasy worlds know monarchy as a form of political power, naming a king or similar position as ruler of the land (a dark mage in his tower qualifies, too), few really try to also imagine a feudalist system. Martin’s take on this is almost unique. Before I want to show how he does it and why he is almost the only one doing it, let’s take a brief look at what feudalism is.

|

| Feudalism, bitch! |

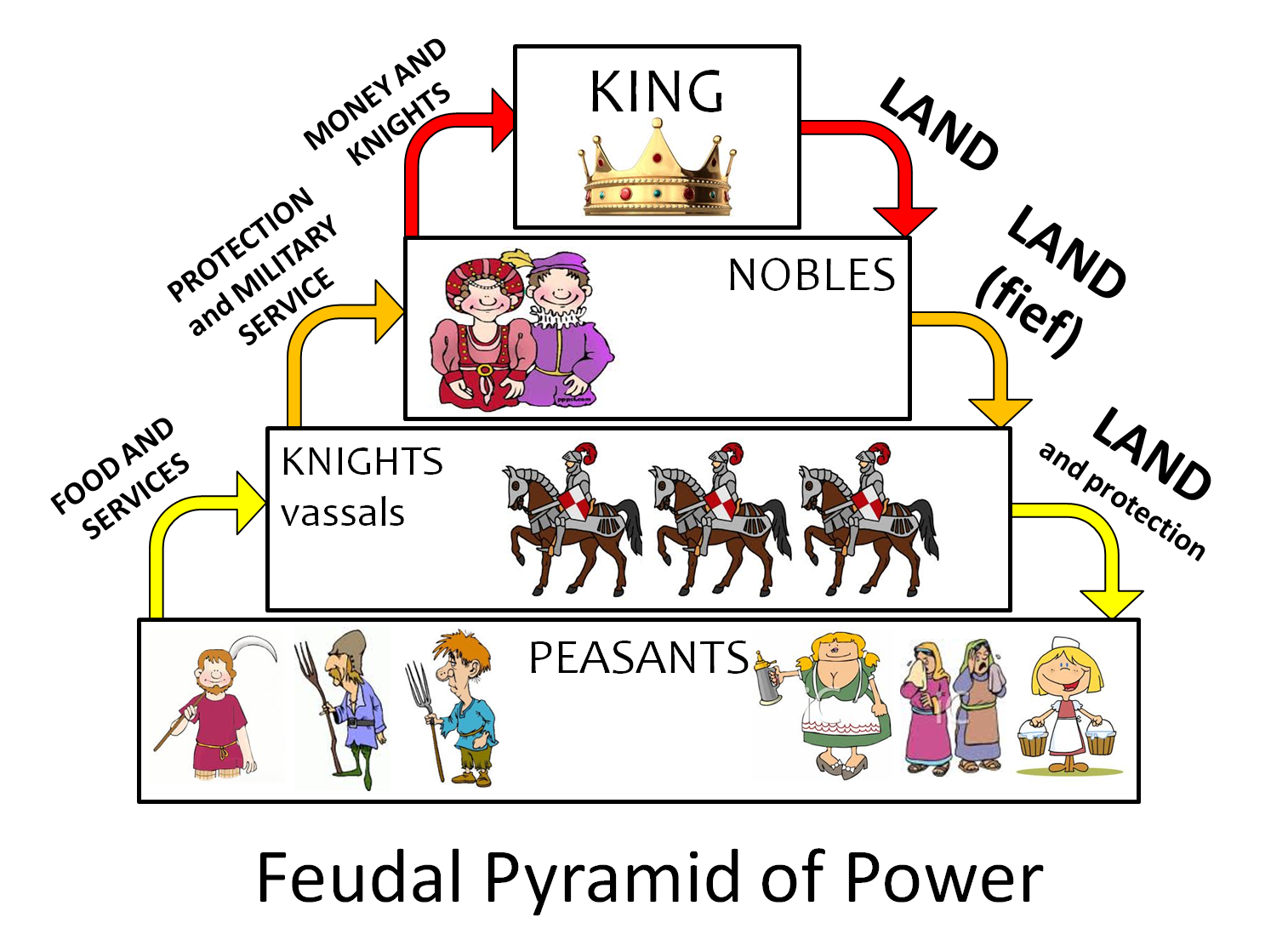

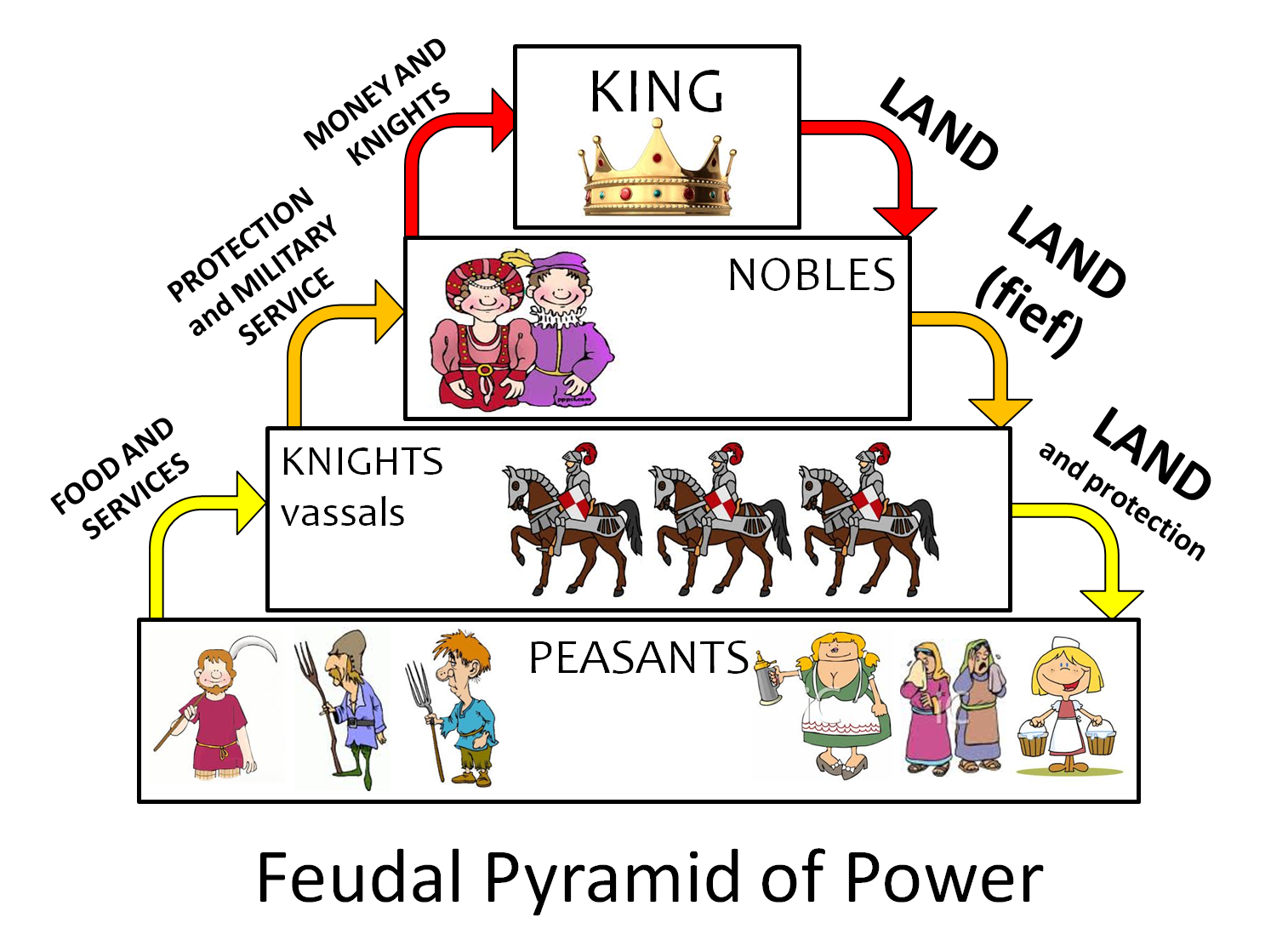

Feudalism is commonly used to describe the political system of the middle ages. As a disclaimer: There is much debate around historical scholars as to what extend this system really existed, since our sources are bad and theory and reality may differ more than we care to admit. It’s also clear that there as many “feudalisms” as there are nobles around, so we’re talking about a bit of a simplified model here. With that out of the way, let’s go in the middle of things. The feudalist order is most commonly depicted as a pyramid, with the highest ranking monarch (usually, but not exclusively, a king) at the top. All lands technically belong to this monarch. Since the monarch can’t possibly rule these lands by himself (bureaucracy didn’t exist until way into the 18th century), he “lends” pieces of the land to other nobles. In return, these nobles swear him an oath of fealty and need to provide certain services and goods for the monarch. For example, the North it “lent” to the Starks by the Iron Throne. In return, the lord of Winterfell has to go to war when the Iron Throne calls him. It may also be possible that he has to pay some kind of taxes or a share of the customs, although in Westeros, the crown seems to sustain itself from the Crown Lands.

|

| The pyramid, simplified. |

Now, our pyramid has gained a second story below the top. We have nobles that are sworn to the king in return for their land. But these nobles still have chunks of land way too big for them to govern. So, they repeat the process and add another level of lower nobility below them to whom they “lend” the land and are sworn fealty in return. This process can (and will) become more differentiated, since the lower nobility can again “lend” parts of their land, until we reach the lowest stage with the Landed Knight, but you get the idea). Our pyramid has now three levels in the simplified model. At its (very broad) base we find the commons. They don’t own land, and they can’t, since technically it belongs to the king. Instead, they are also lent the lands they work on by the nobility one rank above them. Since they are no nobles, they don’t swear fealty. Instead, they are thralls, bound to their noble. Their rights are very much restricted – they can’t move or marry without permission and have to perform certain duties and pay taxes. Commoners who aren’t thralls, like the people living in the city or even rich merchants, don’t have these duties and restrictions, but they still don’t own lands or titles, which severely restricts their social standing. Technically, a low lord could boss around the richest merchant in the land. Technically.

|

| The money stops here. |

In most fantasy, you don’t get this pyramid. Instead, they use a more or less modern state and exchange the elected president with a hereditary monarchy. The state oftentimes has armies, bureaucracy and an extensive grasp on its people. None of this is true in feudalism, and we can see this in Westeros. The Seven Kingdoms aren’t a “state”. No one feels like his identity is “Westerosi”. This is just a denomination from Essos. Instead, people belong to the lords on whose land they live. A peasant at Winterfell will name the Starks, and declare himself a “Northener” should he ever encounter someone from outside the North (which isn’t really likely).

|

| Some people are more...north?...than others. |

At this point, you could simply say thank you for the history lesson and walk away. You read the books, so you probably knew this already, right? Yes, but the feudalistic society Martin envisioned has several consequences that change the whole dynamic of everything that happens within this world. And it is astonishing to which degree he works this in. The first thing is a simple narrative point: it makes the whole story incredibly complex. If you ever read about medieval history, your head probably hurt at some point from all these names with their numbers attached (who was Edward II again in relation to Henry VII?). The same is true for “A Song of Ice and Fire”, because so many characters are running about and playing important parts just because of their station. You can’t simply ignore them. In “Lord of the Rings”, Aragorn was king of Gondor, so Gondor followed him to the gate of Mordor. Imagine Robert calling the banners to fight the Others on the Wall. Can you imagine armies of Dornishmen, people from the Reach, the Westerlands, the Stormlands, the Iron Islands, the Riverlands, the Vale of Arryn and the North marching there side by side and heeding his commands?

|

| Or solve their differences by voting. |

So many plot developments in “A Song of Ice and Fire” happen because of the feudalist system and the tensions it creates. Imagine everything that revolves around the Frey family. Technically, they are sworn to the Tullys of Riverrun, who in turn are sworn to the Iron Throne. When the Tullys rebel against the Iron Throne, house Frey stands at an impasse that is created by the feudal system and cannot be solved by compromise: they have to choose between two conflicting oaths. All lands derive from the king, even their own. That means, that – ultimately – they own their king allegiance. Normally, the king doesn’t ask them directly but goes through their overlords, the Tullys (when calling the banners, for example). But the Tullys rebel against the Iron Throne, breaking their oath. Do the Freys now break the oath to their direct overlords and join the king in his attempt to bring down the rebels, or do they honor their more personal relationship and break their ties with the Iron Throne, too, making the Tully cause their own? Both sides can rightfully expect the house’s allegiance.

|

| Although, come to think of it, perhaps you should just kill them all. |

This choice is by no means easy, and there is no “usual” route. In regions that are more detached from the Iron Throne, like the North, Dorne or the Iron Islands, the lords will follow their direct overlord 99 out of 100 times (as we can see in multiple examples from the Greyjoy rebellion to the War of the Usurper to Daeron’s conquest). It’s a different matter in the other kingdoms, where the ties to King’s Landing are felt more directly. So our first question has to be: why are these ties stronger in some regions than in others? Here the first characteristic of feudalism comes in. Everything depends on the person. If a charismatic US president would choose to send the army against the Wall Street because he needs some money for his castle, the army could and would rightfully refuse him – they swear on the constitution, after all. But in Westeros, oaths are made to persons. Remember when Robert dies and Joffrey summons his likely enemies to court to make their oath at once? He doesn’t summon everyone; it suffices when the oath is renewed when the occasion arises. But you want important people to make the oath as soon as possible. Bear in mind, however, that the oath is only renewed here (which is why not everyone needs to swear to every king). Nominally, the person of the king gives our all lands and receives homage for it automatically. But if in doubt, let the people swear. It’s a powerful display of true allegiances. You can’t easily rebel when you just swore, and if you don’t swear, you state your intent of rebellion for the world to see.

|

| By chopping someone's head off, for example. |

I always come back to the fact that you swear the oath to a person. If a family dies out, all oaths die with them. For example, if the Targaryens had all perished in the tragedy of Summerhall for some reason, the Seven Kingdoms would have lost their overlord. They could have created a new one, but there was no fealty left. At this point, almost always bloody struggle ensues. Since there will most likely be someone who wants to take up the reins, he needs to make a case of why he can do it. And in Westeros, you can’t simply say “because I can” and sit your arse on the throne. If you do that, you need everyone to swear fealty again, and why should they? Instead, it’s better if you can claim that fealty is owed to you because the oaths extend on your person. And here heritage enters the game.

|

| How did his picture get in here? |

Heritage is a simple concept in theory. The oldest son inherits all lands and titles, rights and obligations. Everything goes on as before. In reality, however, there may be conflicts. If there is no son, for example, who inherits then? Technically you just need to trace the line to the next male member, of course. But oftentimes, cases are made for both parties. Imagine Casterly Rock, for example. Tyrion is disinherited, Jaime can’t inherit because he’s in the Kingsguard. Cersei is a woman, she can’t inherit. Who will now? Kevan, as the eldest brother of Tywin? Lancel, as Kevan’s eldest son? Daven, as the eldest Lannister who gives a fuck? If they all want to, who will solve the fight? They can’t do it on their own. So either they risk a fight and simply call on their subjects to support them, or they risk the judgment of the king, which can be a risk in and of itself since the king could decide to exploit the situation and to lend to someone else entirely. Conflicts like this arise all the time. Another striking example are the Hornwood lands. All members of the family are dead, and Boltons and Manderlys both make cases why it should belong to them, with Bran presenting the option of legitimizing a bastard.

|

| Clever lordling. |

That’s why having a legitimate heir becomes such an importance to so many people in the series. If you don’t have a legitimate heir, your house is in real trouble when you die, and the people of this day and age think in dynastic terms (remember Tywin’s speech to Jaime in season 1 of GOT: all that lives on is the family name, individual feats soon forgotten). So, nobody wants to see all he has worked for reduced to nothing. When there is no direct heir (an eldest son), then one needs to search who has the best claim. In some cases this is easy (when there is an elder brother), but as soon as relatives become more distant or, of all cases, female, you have conflicting interpretations. There is no canonic heritage law in Westeros, so you can’t simply open the page, look at article 35, subsection 7 and have an answer. You have to sort it our yourself (see how many of your bannermen support your claim) or appeal to the overlord. Both methods have their challenges.

|

| Legitimizing that guy in the back seems to be a pervasive plot point. |

Let’s take house Arryn as an example. Littlefinger could of course appeal to the Iron Throne to confirm Harry the Heir or even himself as the lawful ruler, but the Iron Throne has at least two reasons not do comply with his wishes. First, such situations offer chance for gain, so the Iron Throne might want something in return from the new ruler of the Vale (taxes, lands, services) that you don’t want to give. Second, a decision from the Iron Throne is bound to leave some guys unhappy, so you might want to let the vasalls sort this out themselves. If the Iron Throne has no strong interest in who the next ruler is, therefore, it’s most likely that the matter will be resolved in the usual way: the contenders have to marshal support. In case of the Vale, it’s clear who will be the next overlord – Harry the Heir – but it’s not clear who controls Harry, so there’s a contest going on that can quickly become hot. In the North, on the other hand, there are no legitimate heirs of house Stark left, so the Iron Throne needs to raise someone else as overlord. It chooses the house that helped them most (Bolton) but really gives them no assistance whatsoever in securing their new claim. One can interpret this in a way that the Iron Throne doesn’t care about the overlord of the North as long as he swears fealty to the the throne.

|

| Fealty? I'm familiar with concept. Nice idea. |

This leads us directly to Wyman Manderly’s plot. I have always come out strongly against various conspiracy theories that the northern lords somehow want to elevate Jon to the King in the North. The King in the North business is done. But Manderly, who in “A Dance with Dragons” states to Davos that he wants to make the last surviving male member of the Stark family, Rickon, the new lord, has a point. An unsuspecting reader might think that Manderly wants to continue Robb’s rebellion, just with Rickon in the front instead of Robb, but that’s not how it works. Imagine he really betrays Bolton, succeeds and throws his lot with Stannis. Stannis is nothing to Manderly, so provided he really has the chance everybody thinks he has – none – he will soon fall. But, Bolton will be over. Manderly could offer the Iron Throne a nice bargain: confirm Rickon Stark as lord of Winterfell and Warden of the North, and in return the whole North will swear fealty to the Iron Throne, with Manderly personally bringing Rickon to King’s Landing to swear in person. The king has the oath he needs, the swords of the North are his again, Stannis is defeated, and the realm is at piece. Instead of Bolton, you have Stark, but why should they care as long as the oath is upheld? Such tactics are used all the time. It is important that fealty is given, not who exactly gives the fealty.

|

| Jolly schemer. |

It is, however, important that one person – the lord – swears fealty. And if said lord is incapable, that can potentially be ruinous. To stay with the Rickon example, we know the boy is rather feral and aggressive (although Manderly doesn’t), so forming him into a capable lord is a hard task that’s likely to fail. The North could be in for some really ugly scenes with lord Rickon, scenes that let many wish for Bolton’s “quiet land, quiet people”. Or look at house Lannister: although powerful in its own right, Tytos Lannister almost ruined it in the course of a generation, leading to at least two rebellions against Lannister rule. Since there is no possibility other than murder or rebellion to displace a ruling lord, you’re stuck with even the most incompetent of lords. And that’s the real bad thing about the feudalistic system: there are no checks and balances. When your lord is gracious and good and capable, you have a good lord for a decade or two. When your lord sucks, you’re stuck with him too. Imagine Ronald Reagan for not two legislatures but ten, and with no Congress or constitution to keep him in check. The guy suffered from Alzheimer, so he would have been utterly at the mercy of his “advisors”, but since he’s the rightful king, there’s no chance to get rid of him. Such situations are the worst fear of any Westerosi, and they are pretty common in this system. Everyone is likely to experience a ruler like that in his or her lifetime.

|

| Some get it worse than others, though. |

Keeping with advisors, this leads to the final problem with feudalism. Of course you could say that the ruler himself doesn’t really matter when you simply surround him with some good advisors and put them in the position to influence the king (Tommen’s Small Council being a prime example of how the king can’t outlaw beets, for example), but in reality, the vassals will not sit idly by and try to influence the monarch themselves. Just look at how the Tyrells try to get a hold of Tommen. A weak monarch is not only prone to make mistakes or be the pawn of his advisors, he also might inflame conflict among his vassals, and being weak in the first place he has no means to put the conflict to rest which could, in turn, lead to war. That’s how many conflicts in a feudalist society start, even though there technically is a monarch whom all are sworn to and who has the sole power about who might wage war. You can see this happening in the Vale with the Lords Declarant: Robert Arryn is on the Eyrie, Littlefinger is the Lord Protector, and both serve the Iron Throne, but they can’t prevent the vassals from teaming up to increase their own influence, and the Iron Throne deems it not worth the trouble of intervention as long as the winners of the struggle swear fealty, which they make sure the Iron Throne knows they’ll do.

And that, in a nutshell, is the effect of feudalism in the world of Westeros.

Brilliant article - it really does well at explaining the feudal system, as well as its significance in ASOIAF.

ReplyDeleteAwesome article!

ReplyDeleteGrreat post thanks

ReplyDeleteI find this exploration into feudalism within fantasy worlds very insightful.

ReplyDelete