When you read the books of “A Song of Ice and Fire”, you will notice that several stories are being told at the same time. The War of the Five Kings is surely the most prominent of them, but the Blood of the Dragon (Daenerys’s story) is another one that everyone knows. The cohesiveness splinters a bit in the two novels constituting the second act of the saga, “A Feast for Crows” and “A Dance with Dragons”, to the point where multiple narrative arcs are pursued at the same time. The same is true for the TV series. And as with the books, the inherent beauty, depth and themes (or the lack thereof) need some examining to be appreciated. In the following, I will have a look at the different arcs in the season and try to submit them to a coherent analysis.

The Shields that Guards the Realms of Men

The first season arc describes the struggle of Jon Snow and Samwell Tarly as our main Point-of-View-Characters to keep the Wall together and to somehow strike an accord with the wildlings that keeps them from being recruited into the growing army of the Undead. As with practically every story, the complexity from the books has been watered down to fit with the serialized format. There is almost no involvement in Stannis’ campaign except for the very beginning. While Sam is trying to get the struggle into a more historical and holistic perspective, this part is set up more as a trial for our hero, Jon Snow, who refuses to get entangled with Stannis, Davos and Melisandre in turn. The proverbial “three temptations” (duty, doing the right thing and sexualized magic in this case) are turned down so Jon can concentrate on the issue at hand: winning the election as Lord Commander and start preparing the defense of the Wall against the enemy of mankind as Stannis, the False Hero, rides off to fight his war.

It is before he can secure his election that he loses his first battle. Neither can he disavow Stannis from killing Mance Rayder, nor can he convince Mance to bend the knee and unite with the Watch against their common foe. This disappointment will haunt Jon, and he is deeply unsatisfied with Stannis’s strategy here, to the point where he decides to do the right thing and end Mance’s suffering by shooting him during the burning ceremony. The hope is that Mance’s second in command, Thormund, will be more malleable despite the cruel execution of his former boss.

The election to Lord Commander is won due to an appeal of Sam to the qualities Jon has, juxtaposing a new beginning and hope for a better future against the dogged “business as usual” that Alliser Thorne represents. For a fleeting moment, Jon is able to secure a broad coalition when he incorporates Alliser Thorne in his command structure and makes no difference between friend and foe. The peak of this development is reached when he executes Janos Slynt, who loses the support and protection of Alliser Thorne, who instead backs his new Lord Commander.

However, soon enough, the main issue comes up: what to do with the wildlings? Jon tries to convince the Watch that leaving them out there to die will make their next task harder, but old prejudices die hard. Even his closest friends do not follow him onto this new line of thinking, as Dolorous Edd evidences when he speaks out against Jon at the big meeting. However, at least in one area Jon can make inroads: he convinces Tormund to join forces with him, and he tells him where the Free Folk went and how to get them. Jon needs to come with him to Hardhome.

Hardhome itself provides everything at once. We get a sense of the importance of the mission as the White Walkers and their army of ice zombies represent a danger to all of humankind, even the Boltons and Lannisters. At the same time, we see Jon triumph in rescuing hundreds of wildlings and killing a White Walker himself, firmly establishing him as the hero. Simultaneously, however, that initial glimmer of hope is brought to naught when we see the great antagonist, the Night King, raise all the fallen as new members of his army, making it even larger than before. There is a clear agenda that needs fulfilling in the time to come.

In the meantime, Sam tried to protect Gilly from the baser instincts of the Watch, proving himself a hero in his own right when he stood up to his brothers to protect her, and their relationship enters a new level when she sleeps with him. Their sex isn’t one of deep love, but great affection and care for each other. The relationship between Gilly and Sam is more complex than some critics give it credit for, as this is neither a pure reward sex on the lines of a classic James Bond movie nor is it that she now sees his qualities and falls in love with him and he with her. He is still bound by oath, and she still knows it.

When Jon returns home, he faces a disgruntled base that shuns him at every step but doesn’t actively oppose him. The wildlings, for the moment, seem too weak and exhausted to play any major role in anything. Sam, drawing a logical conclusion from his own dabbling at the Wall, his shortcomings as a warrior and the deep responsibility he feels for Gilly and the child she named after him, asks Jon to rescue his life and send him to the Citadel. Both of them know that whatever useful skills Sam can acquire there, they will come too late to make any difference in the War for the Dawn. Fittingly, the scene plays out as a goodbye more than anything and serves with a highly personal and touching motive for Jon to be deserted by his last friend and left alone.

When Sam was Jon’s Marc Antony, being kept from entering the Senate House on time to rescue his friend Caesar, then Olly is Jon’s very own Brutus, luring him into the trap with a very personal touch. Jon, hearing that his uncle Benjen has finally been found, immediately and without regard for his own safety runs out into the arms of the conspirators who, instead of leaving him outside the Wall to die with the wildlings, now adhere to that oldest principle that we learned back in the very first episode: they who pass the sentence swing the daggers. Like the senators in Rome, they descent on Jon, making sure he receives every thrust in the knowledge that they are doing it “For the Watch”, beginning with the person of highest authority (Thorne) and ending with the most innocent (Olly).

As Jon lies in a puddle of his own blood, his eyes broken and dead, the audience is left to wonder: Will the wildlings rise against the Watch or vice versa, or will the truce hold? And will Melisandre, whose timely arrival only hours before the assassination opens new opportunities revive Jon like Thoros has revived Beric Dondarrion? There is not much doubt that Jon will come back. He has established himself as a leader and hero in this season’s arc, and he is desperately needed to fight off the White Walkers when they arrive. The question is whether or not his rise from the dead will trigger a civil war.

The Shields that Guard the Realms of Men are torn between loyalties and urges, between what needs to be done, what is right, and what the people around them expect them to do. They are much more progressive than the people around them, visionary even, and they are trying to do their best to rescue humanity. It is not enough, however, as they are not able to overcome the conservative forces that cannot accept that the situation has changed. When Jon returns, it can be assumed that he won’t care that much about the rules or the consent of his brothers anymore. The ends may justify the means for him then, and it is not by accident that we witnessed another arc this season where exact this approach leads to the downfall of a False Hero.

The False Hero

Stannis Baratheon starts the season in a strong place. Having singlehandedly saved the Realms of Men from the onslaught of the wildlings at the end of season 4, he is now trying to leverage this into help for his own campaign. As Davos advised, he put his duties first and his rights second, and now he expects the rewards from this. While he is making plans to wrestle the North out of the hands of the Boltons, he is administering the defense against the White Walkers. Not only does he allow Jon to try and convince Mance to give up, even promising to spare his life in the event, he also recognizes the strengths and weaknesses of the Watch, encouraging Sam to “keep reading” while dismissing most of the grammatically uneducated Watch men.

However, in the end, he is turned down by Jon. Faced with the options of staying and manning the Wall against the White Walkers or to try and finally get his throne, he chooses the latter, but not without showing us his human qualities as well as his leadership skills: the love he feels for his daughter is sincere and touching, and we get lengthy exposure to her lovable kindness as well to develop a bond with her. In between all this is Davos, who tries to forge an alliance between Stannis and Jon and fails, and who tries to keep Shireen out of harm’s way and fails yet again. His third failure will come later, when he can’t convince Stannis to abstain from going down a dark route.

Stannis, meanwhile, is edged on by Melisandre. While undeniably powerful, the Red Woman herself fails in her attempt to enthrall Jon the same way she did Stannis, way back in season 2. This should have told her enough already about the true incorporation of Azor Ahai. How can you expect someone who totally falls for a witch like her to be the hero of an aeon? But committed to Stannis, she edges him on, roughing over any doubts that could be left, weather and odds be damned.

And so Stannis rides out in the winter snows, thrice ignoring the counsel he gets from Davos: he doesn’t leave Shireen in Castle Black, he doesn’t turn back when the snows prove unconquerable, and he refuses to send Shireen with Davos again. Stannis’s conviction that the only route left to him is forward is a mirage, induced by his own stubbornness and conviction that he needs to do the things he does for the good of mankind, all the time edged on by Melisandre, who is like the cartoon devil sitting on his shoulder and whispering bad advice. Like many cartoon figures do, Stannis sends the opposing good angel away, giving way to the bad one.

What follows is basically an analogy to the original Star Wars trilogy, a theme that is surprisingly mirrored in Arya’s arc. Stannis grasps for the powers of the dark side because they are quicker, easier, more seductive. As he soon learns, though, they are not stronger. Stannis should have listened to Shireen, wisdom from the mouth of babes: When it seems like there is only one way to go, when it seems like you have to make a decision you really don’t want to make, then may simply be untrue. Stannis has another option. He can go back, and do his duty to the realm. But he thinks that going back is never an option, that the only route is forward, and thus he gives in to Melisandre’s counsel. Ramsay burning the supplies is a more potent sign, but Stannis misreads it. Instead of questioning Melisandre’s qualities as a prophet, he doubles down on her.

When, the morning after the burning, he wakes up to half the army having deserted him and his wife dead, whether from suicide or murder, both he and Melisandre have an epiphany. They both recognize that he is not, in fact, Azor Ahai. Melisandre cuts her losses and deserts him to try and throw herself to the man who, in fact, is, but she comes too late to prevent his murder. Stannis, meanwhile, without horses, men and supplies, still knows only one way: forward. He marches to Winterfell to meet his doom, and his army is hacked to pieces. When he himself lays wounded in the woods, ready to die, his earliest crime catches up with him. Brienne of Tarth steps out of the trees, and Stannis confesses to kinslaying, a deed the gods will never leave unpunished. As Stannis has told Davos – and the audience – several times: “A good deed doesn’t wash out the bad.” True to himself to the end, he urges her to “go on and do your duty”.

The False Hero goes down because, ultimately, the ends do not justify the means. This is not a story about overbearing ambition, as has sometimes be claimed, nor is Stannis’s death simply an act of pure shock value to boost ratings. Stannis’s demise is a cautionary tale. With Jon, Tyrion and Dany all poised into positions of power and decisive leverage, they would do well to heed the example that Stannis gave them. Protecting the world doesn’t merit destroying it in the process. This is the lesson that Stannis failed to learn, and it is what brought him and everyone around him down. The cost of failure is high, as the retinue of Eddard Stark learned to their sorrow when they met pointy ends.

The Princess in the Tower

Sansa was for the better part of season 4 locked into the highest tower of Westeros. Only in the end did she seem to grow wings, metaphorically underlined by her feathered dress, and leave the Eyrie together with Littlefinger and Robin Arryn to new adventures. She had fearlessly sat opposite to Lord Royce and Lady Waynwood, and it seemed only natural that she would now start to play her very own Game of Thrones.

So when Littlefinger approaches her with the idea to marry Ramsay and, being the master schemer that he is, points to the safety mechanism against Ramsay’s renowned cruelty that will protect Sansa, she agrees to further advance their common goal. Arriving in Winterfell, a gripping cat-and-mouse-game ensues in which both sides know that they hate each other but no one can make an obvious move for political reasons. – Just kidding, of course.

In the event, Littlefinger proposes Sansa to Ramsay to create a new alliance which he already wants to betray with a switch to the False Hero whom he sees most likely to end out on top. Sansa is nothing but a pawn in this game and is manipulated by Littlefinger into playing along. It is a rare showing of his social acumen when he gives her a false choice about going through with the plan where there is in fact none, and soon, Sansa finds herself in a room with the man who killed her brother.

In the short engagement phase, Sansa is indeed trying to hold her own against the Boltons, using stabs against them when she can. She is helped in this from outside: Brienne found some Stark loyalists who make contact with her, and even in the castle, an old woman still remembers. It seems like the Stark heritage is her strongest protector, and that Ramsay would be a fool to go against it openly, restrained by his father. Sansa also learns of Theon’s fate, who is caught in his Reek persona, but she makes no attempt to connect to him – he is the other person in Winterfell who killed brothers of hers, after all.

All of this is rendered moot after the wedding, however. Ramsay shows his true colors and abuses Sansa, locking her away in her chambers and abusing her further as he sees fit, without any repercussions. Indeed, he will even become the nigh invincible enforcer of the False Hero’s downfall, showing nothing more than, yes, evil will triumph once again. When Sansa finally manages to get a light lit in the tower to call down her white knight Brienne, it is too late. Unlike in King’s Landing, there really was someone who truly wanted to save her, but that person chose her older oath, her quest for revenge, over the newer oath that she swore Sansa’s mother, and so that avenue is foreclosed. Instead of rescuing herself, Sansa, bereft of the possibility of a rescue by Brienne, is instead saved by Theon who finally shed his Reek persona because Myranda threatened her once more.

The Princess in the Tower, therefore, fails because she is denied agency more than anything else. She is not allowed to trade either her status or her considerable force of persona to her advantage, both of which she used to great effect in season 4. Instead, she reverts to the status of a victim, abused by super-villain Ramsay, and serves as a motivation for Theon to finally break free. Her wings have been broken, and it will be for a later season to mend them again and to take up the thread where this season lost it.

The Sparrow in Her Hand

The death of Tywin Lannister at the end of season 4 presented Cersei with something Littlefinger could surely appreciate: a chaotic situation in flux, in which no one is certain who is friend and who is foe, who is player and who is a piece. Mistakes are only natural in this situation, and mistaking the nature of the game being played is an all too common one. Cersei can find consolation in the fact that Margaery made the same mistake.

Both queens start the season by thinking that this is their time, a showdown between queen and queen regent, with the favor of Tommen Baratheon as the main instrument of this conflict. And this is how it plays out at first. Margaery, using the more subtle methods of personal charisma and popularity, woos Tommen into loving her deeply, but fails to make use of him. While Tommen is easily gullible and can be pushed into repeating Margaery’s words, that some weakness makes him lacking as a tool, since a stern word from his mother suffices to shatter his self-confidence and let him stutter out. Margaery’s attempts at sidelining Cersei therefore don’t lead up to much other than embarrassing Cersei in public, which Margaery in a stunning display of political naiveté takes as a genuine victory.

Cersei, in the meantime, lost no time in securing the real levers of power and stripping the Small Council of anyone who would threaten her rule, real or imagined. Driven by the prophecy she received as a young child, she installs her own patsy Qyburn as Master of Whisperers, sends an ineffective Mace Tyrell to Braavos so he can’t bring the power of house Tyrell to bear, puts Pycelle ins his place and sidelines the other Lannister pretender, Kevan Lannister, who retreats to the Rock in disgust. Having thus firmly established her own hold on power, she jumps into the tug-of-war with Margaery over influence over Tommen, but the stalemate can’t be broken with the means of courtly politics as both sides can’t openly attack each other – a development that should’ve been mirrored in the North by the Princess in the Tower but wasn’t.

Instead, Cersei resorts to make use of the new power in town: the religious devout. While she knows that Margaery and Loras are both easily vulnerable by religious zealots for the hedonistic way of life the Tyrells enjoy, it’s also a giant gamble since, as we were reminded by Lancel in episode 1 of the season, she isn’t exactly a paragon of virtue herself. For the moment, however, it works. She crowns the High Sparrow as new High Septon, giving him all the power he needs to establish a firm regimen of the devout and create a crisis by imprisoning Loras. Littlefinger would approve the principle, but surely not the means, as a chaotic crisis that threatens the foundations of noble power isn’t a gambit worth taking, as Cersei will soon learn.

Instead, Cersei resorts to make use of the new power in town: the religious devout. While she knows that Margaery and Loras are both easily vulnerable by religious zealots for the hedonistic way of life the Tyrells enjoy, it’s also a giant gamble since, as we were reminded by Lancel in episode 1 of the season, she isn’t exactly a paragon of virtue herself. For the moment, however, it works. She crowns the High Sparrow as new High Septon, giving him all the power he needs to establish a firm regimen of the devout and create a crisis by imprisoning Loras. Littlefinger would approve the principle, but surely not the means, as a chaotic crisis that threatens the foundations of noble power isn’t a gambit worth taking, as Cersei will soon learn.

For the moment, however, she uses the Sparrow in Her Hand to great effect. With Loras imprisoned, she lures Margaery into a trap and outfoxes Olenna Tyrell, gaining absolute control of the court and castrating the Tyrell power by destroying their follower base and curbing their traditional ways of projecting power. The champion of the people, Margaery isn’t anymore. However, Cersei misunderstood the nature of the game being played, and so did the viewers, who were lured into the same trap of complacency with Cersei’s self-constructed narrative. The Sparrow in Her Hand is not, in fact, a piece, but a player himself. The first to notice this to her own shock and dismay is, of course, Olenna Tyrell, who tries to reason with the High Sparrow only to realize that he is a true fanatic and can’t be argued with. Shell-Shocked, Olenna falls in virtual apathy.

It’s Cersei, though, who soon enough has to learn that some doors are better kept closed. Since Lancel spilled the beans about her crimes to the High Sparrow, the latter imprisons her after her greatest triumph over Margaery in a cell next to her. Cersei’s fall is steep and deep, and soon she is licking water from the filthy floor, trying to preserve what is left of her dignity. Of course, her dignity is exactly what the High Sparrow is after, and so she is forced into a Walk of Shame to destroy her reputation and what makes her what she is. The brutal marsh through King’s Landing nearly breaks her, but in the closing scene of the Red Keep we see that she at least kept the one lesson that she gave Littlefinger in season 2 and that Margaery and the High Septon have yet to learn: power is power, nothing else. Pycelle can gloat as he wants, Cersei was right to keep control over the levers of government and build up her own secret force, one that will now defend her in the trail to come – a trial in which Margaery lacks a defender for the nonce.

The Sparrow in your hand, a saying goes, is better than the pheasant flying by. While Margaery reaped little joy of the fleeting pheasant’s flight of public popularity, Cersei didn’t that much enjoy the Sparrow in Her Hand either. While one of The Breakers of the Wheel in far-out Meereen is dabbling her feet into the forceful current of political change, the Sparrow in Her Hand is already exerting it in King’s Landing, threatening the very fabric of Westerosi society.

The Stranger

After having seen his son die, getting estranged from his sister and lover and then being responsible for the death of his father, Jaime is finding himself in a strange place. Having lost all that once made him who he was – a fearsome warrior, respecting nothing and taking what he pleased – he now is in King’s Landing, unwanted by his sister, unacknowledged by his children and unable to do anything useful. Full of regret over his failure to prevent the assassination of his son, he now wants to make up for it helping Tommen, but Cersei, with a clear sight on the role Tommen plays in legitimizing the Lannister hold on power, doesn’t allow it and only offers scorn for Jaime, who also failed to protect their father. No wonder Jaime jumps at the opportunity to instead rescue Myrcella, who is threatened by the Sandsnakes, seeking revenge for Oberyn’s death at the hands of a Lannister patsy.

The problem is, at Cersei points out sharply, that Jaime is not only bereft of anything useful in an attempt to rescue her, he is also an active hindrance to anyone trying in earnest. Instead of trying the more realistic and success-inducing route of officially going to Dorne as an envoy, Jaime recruits the swaggering Bronn to his cause and starts on an adventure from the golden age of cinema in the 1930s, with sword fights, gags and omnipresent confidence in the plot armor to carry you through. This is an approach that might have suited the Jaime Lannister of old, but this man is a stranger to him.

After arriving in the strange land of Dorne, Jaime and Bronn sneak into the palace where they find Myrcella quite enamored with her new lifestyle and, especially, her betrothed Trystane and refuses to go along. Luckily, the embarrassment is relegated to the back seat when the Sand Snakes show up in an attempt to abduct Myrcella themselves, only to be captured by the palace guard.

Now an envoy at last, Jaime learns that he had only to ask for Doran to send Myrcella home, while Bronn learns that the Sandsnakes aren’t fearsome warriors but in truth only teenage girls who want to play with dangerous objects, which averts much of the danger. However, no one seemed to think that the vengeful Ellara would ignore Doran, whose view on good governance equals the instincts of his teenage son Trystane serving out a good smack in the face as a proxy for meaningful action, and kill Myrcella anyway. This of course aborts the bonding of Jaime with his long lost daughter, who dies in the moment she acknowledges her father and gives him the glimmer of hope for a new identity.

The Stranger, therefore, remains strange not only to himself but also to the land he travels. In the end, he resolves nothing, as he dares nothing and doesn’t think through his plans. Instead of maturing by taking up the responsibilities of actual politics, he tries to play pirate and to abduct the princess, and the plan backfires horribly. So too does this plot, which leaves Jaime in more or less the same place he was before, a Stranger to himself, those surrounding him and the viewers alike, but at least on the road to home.

The Blind Girl

After Arya left Westeros in one of the few triumphant moments of season 4 in the closing shot of the final episode, she now arrives at a foreign place. The looming and intimidating House of Black and White doesn’t offer the hospitality and safety that Arya had hoped for, and she doesn’t find Jaqen to open the door for her, but a stranger she never saw before. He sends her away, and even though Arya tries to show resolve by waiting in front of the door through rain and sun, she finally gives up her attempt and wanders the streets of Braavos, where the stranger from the temple prevents her from getting into a fight with some braavos for no discernible reason. What has she done to merit entrance to the temple after all?

It remains unclear, but we see that Arya is a Blind Girl – as is, in extension, the audience – because she wasn’t able to tell that the man from the temple is in truth Jaqen H’ghar, who is in truth No One. The Blind Girl, of course, proves blind once again, not remembering what Jaqen told her before he left her at Harrenhal: the powers he possesses can only be reached through great sacrifice. The Blind Girl thinks that this is still her buddy assassin, but she’s gravely mistaken.

Soon enough, though, she has to learn that No One isn’t her friend, but a hard and unforgiving mentor. He sees potential in her and allows her to race the ladder, much to the chagrin of the waif, but climb it she still must. While blind, the girl does understand the outer workings of the House of Black and White, and when she proves to be an apt liar in a beautiful scene with a terminally sick girl and shows the compassion needed to do god’s work, she is introduced in the inner workings of the temple. She now has to become No One, but blind as she is, she doesn’t really understand what this means. For her, it’s about becoming a good enough liar so No One will accept that she is No One, too, but that isn’t enough, and this revelation will come to haunt her soon enough.

For the moment, though, she can see what is done with all the dead and why the faces are kept in the temple. Presumably, using them is easy and requires only putting the face on, since she will later use it in her plan against Ser Meryn, but for the moment, Jaqen and the waif train her for her first mission, in which she will need to assassinate an unfaithful insurer. Before the Blind Girl can commit further to becoming No One and fulfilling her task, however, fate throws her a curveball from her past. Mace Tyrell arrives to treat with the Iron Bank, and in his retinue, he has Ser Meryn Trant, one of the few to remain on Arya’s list.

The Blind Girl, deluding herself that she isn’t watched at all turns, abandons her mission, lies (badly) to No One and engages Ser Meryn, using his vice of raping young girls by masquerading as the little girl she gave the gift of the Many-Faced-God to, going against everything she should have seen and learned by now. However, despite utterly failing on the ideology, she carries out her mission with great efficiency and care. She is not content with only killing Ser Meryn; this could have been achieved in a myriad of subtle ways that would have stood better chance of going undetected by No One.

Instead, she commits to her past as Arya, fully embraces the hate that she feels. Blind with revenge, the Blind Girl lashes out at Meryn, blinding him in turn. The method of execution is carefully staged. Meryn loses his ability to see, just as Arya has lost hers, albeit in a more physical manner, and then has to learn exactly who kills him and why, both anathema to the Faceless Men the Blind Girl thinks to imitate. When she returns to the temple, therefore, she sees for the first time: No One, who she still thought to be Jaqen H’ghar, isn’t even physically one person. Did he die? Did the waif die? Did anyone die? As Arya pulls away face after face after face, she finally uncovers her own, like Luke Skywalker in that cave on Dagobah. After that short moment of seeing and revelation, Arya is now blind again, and in fitting retribution for the fate the gave Meryn Trant, she is now physically blinded as well.

If the Blind Girl really wants to become No One, she now has to commit to it with all her being, without being distracted by the things she sees around her. However, it seems like No One is blind as well. The Blind Girl, while being an adept killer, quick to learn and great at carrying out her new skills, is by no means ready or even willing to become No One. Instead, she is destined to surpass her master, masquerading as No One like No One masqueraded as Jaqen and acquire all the help she wanted to pursue her own goals. The problem with blindness is that you can’t see it for yourself – you never know what exactly you are looking for. This is a lesson that Syrio Forel surely would have appreciated.

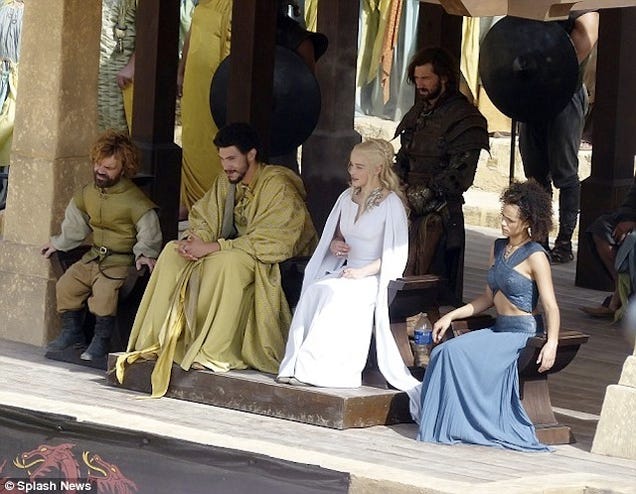

The Breakers of the Wheel

After having conquered Meereen in season 4, Daenerys now faces the dire prospect of ruling the place. Immediately, she has to come to terms with the fallout of her previous decisions. Sitting in her throne room, the wheel of government is keeping spinning. Confronted with the deep grief that the members of Meereen’s ruling elite feel after her gruesome crucifixions, she makes concessions to Hizdahr zo Loraq, a member of the ruling elite that seems poised to bridge the divide between the diehards of the Old Way and the newcomers with the New Way.

However, as Dany soon has to learn, the wheel keeps spinning, whether she wants it or not. The Sons of the Harpy, a terrorist organization formed out of said diehards, attack her people and try to destabilize her rule. When she takes one of them captive, one of her freedman kills the prisoner, thinking he was doing her will, and Dany finds herself between a rock and a hard place. Does she pardon her follower, showing to all of Meereen that justice and the rule of law are mere rhetoric? Or does she punish him for it, showing that she adheres to these lofty principles, alienating her own followers and likely not winning any new ones?

Dany decides to do what a good ruler does, and adhere to the principle. Stannis would have been proud of her, but when she needs to be whisked away from a hostile crowd under the protection of her Unsullied, she has become an estranged ruler without any power base safe for her dragons, and those she already lost. Drogon, who presents the temptation to solve the issue by fire and blood, returns for a fleeting moment to the pyramid, but when Dany tries to touch him, to connect to him, he feels that she is still committed to spinning the wheel and flies away.

Tyrion and Varys, meanwhile, have made common cause. Varys hasn’t convinced Tyrion that Daenerys is a worthy queen yet, but Tyrion at least wants to give her the benefit of the doubt. Appalled by the slavery he witnesses in Volantis, Tyrion sheds his cynicism for the first time when he listens to a follower of R’hollor preaching the day at which Daenerys, the Prince Who Was Promised, will come and end slavery once and for all – breaking the wheel for good. For now, however, Tyrion’s road is twisted, as Jorah Mormont abducts him and takes him on a much rockier road to Meereen than he previously enjoyed, sobering him up in the process and enhancing his own understanding for the greatness and beauty of the world.

In Meereen, Dany is hard pressed to keep the peace in her own city. Trying to connect to her own largely unknown past with Barristan the Bold, a role model for all knights, she sends him out to learn what the people think. This isn’t hard to achieve, as Barristan stumbles into an ambush that the numerous Sons of the Harpy have laid with the help of some inhabitants and gets killed.

Dany now faces the ruin of all her visions and plans, taking it out on the masters of the city, not discriminating between guilty and innocent as she did once before. However, even after burning one of them alive, Dany is still torn between trying to rule the queen by consent and being a butcher queen. Daario’s advice to stage a wedding and kill everyone is right from Roose Bolton’s playbook, and for the moment, Dany doesn’t want to consider it.

Instead, she takes the advice of Missandei. Instead of being boxed in by two seemingly extreme choices as was the False Hero, Dany needs to think outside the box and come out with a new, third way to solve the problem. She does so by wedding the spokesman of the masters, Hizdahr zo Loraq, who urges her to wed not only him but also her customs with those of the city. Therefore, slavery remains abolished, but the fighting pits reopen.

This reopening opens the door for Tyrion to propose his services to her, and while he does so out of a miserable lack of options, the queen can instantly see the worth of the dwarf: just like her, he’s an avid proponent of the third way, and instead of choosing between the false choices of pardoning or killing Jorah, he chooses one that alienates no one. This leads to Dany investigating Tyrion’s wisdom deeper, and both of them find common ground quickly: the world is mess, and somebody needs to rule it. Feudalism is bad, but how does Dany want to reform it? It’s a question that Tyrion tackled but didn’t find the answer to. In Dany, he has the warrior queen to do it: she flat out announces that she is going to break the wheel.

Unfortunately, after stating the mission goal, Daenerys never gets to plan strategy with Tyrion, as her third-way-project is thoroughly undercut. For reasons that remain a mystery, the Sons of the Harpy are not in fact turned down by the marriage with Hizdahr, electing instead to kill Hizdahr and to ineffectually try to kill Dany and her court as well. This plan fails only because Dany is rescued by Ser Jorah and then, of course, the personification of her desire for fire and blood, Drogon, who flies off with her, providing her with the ultimate tool for wheelbreaking. As of season 5, however, she has still to find out how to do this, as she cannot rouse Drogon again and is soon abducted by a band of Dothraki.

The success of Dany’s plan, therefore, rests ultimately with Tyrion. As Dany is impotent in regards of building a lasting peace agreement, as is Tyrion in terms of creating the conditions that make it necessary. Dany’s moral compass and capability to destroy bad things is matched nicely with Tyrion’s ability to take instable and violent situations and transform into something more suitable. Both Breakers of the Wheel have now to work together and trust in the capabilities of the other to do their part.

Conclusion

There are two plot locations in season 5 where there is no real arc discernable: Winterfell and Dorne. Both are, not surprisingly, among the most reviled elements of the season. Another one that starts strong but has to survive a big hit in the end is Meereen, where the giant and all-compassing attack of the Sons of the Harpy seems to happen more because things need to fall apart than because of any major internal logic. Hizdahr and his whole story seem aborted, serving no real purpose other than masking the final reveal.

The point where I think I disagree most with fandom and critics is Stannis’s arc. It follows a thorough narrative logic, and only because it differs from the book (and I am certain that things will play out not like portrayed in the show when The Winds of Winter blow), we shouldn’t be too quick to deny its own inherent qualities.

The question is why Dorne and Winterfell fell apart as they did. In my eyes, Winterfell was a failure of inception. For some reason, the creative decision was to relive the season 2 and 3 dynamic of Sansa and Joffrey, instead of doing something new. The pure execution of this is well done – Sansa’s rape, for example, is set up well and shot perfectly. That doesn’t save what happens later, however. As for Dorne, this was a failure from the get-go. If Cersei Lannister explains to you the reason why your plot is dumb, something is going wrong. In both cases, subtlety would have been warranted, a political cat-and-mouse-game in a hauntingly familiar (Winterfell) or extremely strange (Dorne) setting where the rules are as unclear to the viewer as they are to the characters. Instead, the show in both cases went into the safe direction, and in both cases it was a mistake. It’s like a summer blockbuster in which the executives at one point decided to start shooting because the script was “good enough”. Well, no, it wasn’t.

So, where does this leave us? I think that season 5 presents us both with some of the strongest material and with some of the weakest that the show has ever done. The same is true, funny enough, of season 2, in which the whole plot north of the Wall presented serious problems and where Dany’s plotline was, let’s say, controversial. The problem in any final assessment is that we don’t yet know what season 5 will lead up to, since we neither know “The Winds of Winter” nor season 6. We have a better understanding of the effects of season 2, where Jon’s arc suffered heavily throughout seasons 3 and 4 from the decisions made in season 2. Dany’s arc, on the other hand, proved just pointless in the end, treading water until she was allowed to arrive in Astapor.

I seriously hope that Dorne and Winterfell are “Where are my dragons”-moments for Jaime and Sansa from which they will soon recover by strong writing in season 6 and that no lasting damage is done. Since none of the two requires setup as a character anymore – contrary to Jon in season 2, who needed to be introduced as leader material – the chances for this are actually good, which is why I would place season 5 closely before season 2 and after season 4. Seasons 3 and 1 remain my favorites. I want to emphasize, however, that this is only an evaluation of degrees. In the end, all seasons of Game of Thrones are great TV and fun to watch.

Good piece but I disagree intensely regarding Stannis. I'm not a book snob, but they ruined that character in my opinion. Whatever the man is, he is no fool, he would not have allowed Ramsay freaking Bolton to sneak into his camp with a few other men and burn all his food, then escape without a scratch. He would not have been blind to the very predictable backlash that would come from burning his own daughter alive (Tangent: In the books does Mel ever explain why they need to be alive and conscious when they are burned? seems unnecessary). In ADWD he is reluctant to burn even criminals. He would not have been surprised by a massive army, ahorse, massing at Wiinterfell. Stubborn as he is, he would not just walk to a slaughter, there is a reason they stop marching at that village in the novels. They turned him into an ambitious religious zealot, and that is not the character.

ReplyDeleteYes, show!Stannis isn't book!Stannis. But I'm not interested in a 100% adaption. I evaluate show!Stannis on the basis of the show, not the books.

DeleteI don't need a 100% adaptation either, that is not possible, I do need good storytelling, and presenting him (literally) as one of the great military commanders of westeros only to have him act like an utter buffoon and get humiliated is not good storytelling in my opinion. They could have had him lose and still not look so foolish, that is what I imagine will happen in TWOW

DeleteI don't think he looked foolish.

DeleteStannis arc is simply stupid. The greatest commander of Westeros does a crime that would destroy the moral of his troops, ignore the most basics tactics and finally is destroyed by a colossal army that appears from nowhere and simply does not fit in Winterfell.

DeleteMost of all, his behavior is not coherent. He loves her daughter, he is a great commander, he listens to his advisors,he is considered a great man by Mance, Sam, Jon or Davos in show canon. Then he commits an unforgivable crime killing the love if his life due to a absolutely illogical and nonsense decision, refuses to listen his advisor and behaves like the worst commander of the history of Westeros.

Also, remember that his army is in a difficult position just because "20 good men" destroy the supplies of an army of 5000 men,

The quality of this season has been the poorest of the show, absolutely horrible, tied maybe with some arcs of season 2. And the arcs to blame are Dorne and Stannis. I still want to vomit when I think about what Dumb and Dumberd did with them.

I don't agree.

DeleteI think I, you, and most, have underrated the end to Jaime's arc. He will be a very different character than the books because of having is loving daughter die(?) in his arms.

ReplyDeleteThis is not a defense of how we got to that point, but I think it is worth acknowledging how emotional of a position Jaime is now in relative to beginning of season. I think it is also worth considering how the Jaime/Cersei relationship could be impacted by this. Perhaps their quest for revenge will unite them?

There's now way to tell what the death of Myrcella will do with Jaime, which is why I can't really say anything. It wasn't really prepared over the season, though, and the rest of the story was a jumbled mess.

DeleteI think the death of Marcella is what will end any sort of relationship between Jaime and Cersei in the show. There was already conflict, but Myrcella dying and Jaime being unable to stop it will be the last straw.

Deletewell described.

ReplyDeleteAmazing blog. Game of Thrones Season 7 is coming soon with exciting thriller and story. Watch game of thrones season 7 online . Surely you will enjoy the trailer as am excited to watch this season.

ReplyDelete